Inmates Access to Social Media

24 October 2024, El Paso, Texas, Steven Zimmerman – It’s just after two o’clock in the morning, you’ve closed the restaurant, and you’re walking to your car.

Everything is dark. The streetlights can’t break the darkness caused by the heavy storm clouds. Even worse, you had to park five blocks from the restaurant, near a corner with no lights.

You quicken your pace as you hear noise coming from behind you. As you approach your car, digging for your keys in your purse, you hear a voice behind you.

“Your purse,” the disembodied voice says. “Give me your purse.”

You turn around to see two men with ski masks and hoodies up.

“Your purse,” says the second man. “Now bitch, your purse.”

You panic. Unconsciously, you pull your purse behind you, angering the second man. Before you black out, all you feel is searing pain. Your face and abdomen feel as if you’ve been hit with a sack of bricks.

Two days later, still in pain, lost, and confused, you wake up in the hospital. You scream, remembering the robbery, the pain.

Over the next few hours, your family, friends, doctors, and police detectives explain that you were robbed and beaten, but the culprits are in custody.

“Don’t worry,” says one detective, “they are three-time losers; you’ll never see them again.”

You begin picking up the pieces of your life, scared of everything. You’re a nervous wreck. You can’t imagine ever going out at night again. But you get better, stronger. You recover and begin living life again.

Then, you scroll through TikTok and see a man, an inmate. You recognize him from the trial. The man on your screen is the man who beat you into unconsciousness for twenty-eight dollars, your cell phone, and makeup.

Again, all at once, the fear returns.

It’s hard to imagine the fear of being robbed, going to trial, or seeing one of the criminals again. However, Loretta Hayes has recently experienced this.

“I was told by the police, by the judge, I would never see either of these boys again,” says Ms Hayes, a woman in her seventies. “They were sent to prison; why was he on TikTok?”

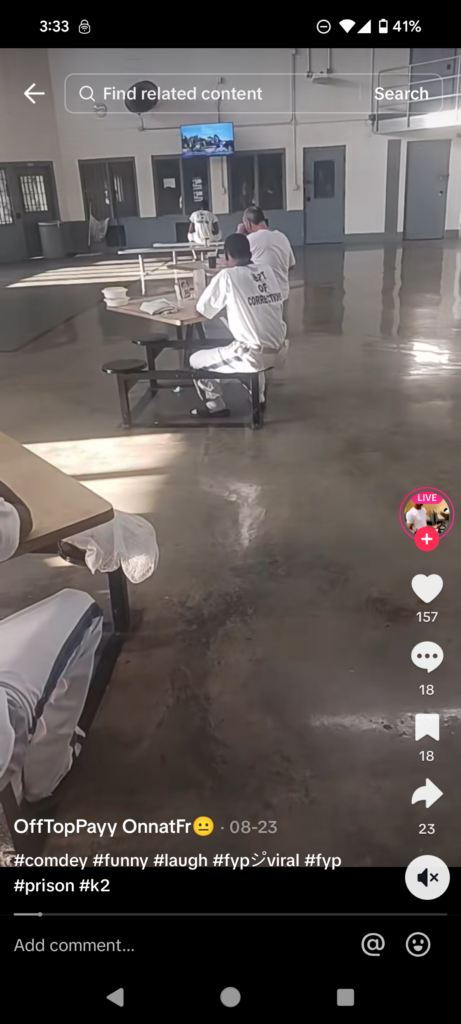

Inmates can purchase tablets in the commissary of state correctional institutions and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These tablets allow inmates to have contact with family and friends, expand their education opportunities, and expand their unities and entertainment such as music and movies.

“These inmates have a lot of time on their hands,” says Robert Rios, a prison guard. “They will find ways to circumvent security protocols installed on these devices, given enough time.”

According to every prison official we spoke with, inmates should not have access to social media.

“If they have access to Facebook, TikTok, or other social media platforms,” says Brian Tenner, a prison communications specialist, “that poses a risk to the community, as well as the safety and security of the institution.”

Many inmates will find ways to continue running their criminal enterprises while incarcerated. Unrestricted access to telephones, such as cell phones, and social media messaging may help facilitate further crime or retaliation.

“We have to look at a situation that occurred a couple of years back,” says Christian Zaragoza, a prison guard in Texas. “An inmate had a cell phone inside the institution. He used that phone to order attacks on rival gang members on our streets. Now tablets are in the mix.”

Texas Department of Criminal Justice officials have indicated that tablets would make communication easier for inmates, provide entertainment, and reduce contraband entering prison facilities.

“The problem is,” continued Zaragoza, “inmates are still going to find a way to get around our rules and restrictions. These [tablets] are nothing more than pacifiers for most inmates.”

While inmates pay for music, television episodes, and electronic messages, we begin to miss the larger picture. Prison staff can be lulled into a false sense of security within their institution, believing that other forms of contraband, such as cell phones, are not present.

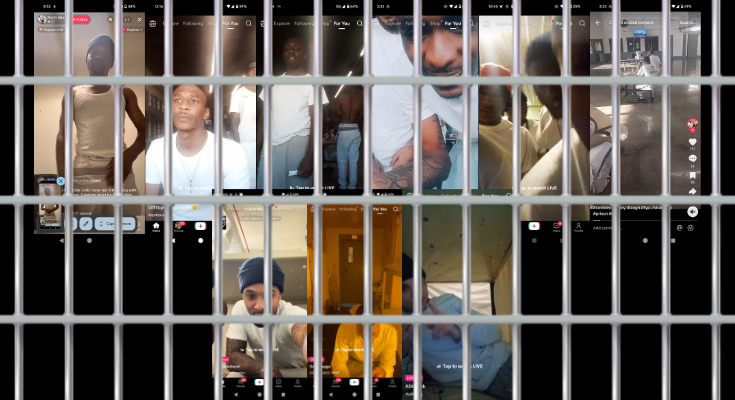

We created an account on TikTok and began searching for inmates. It took us only a short time to find them.

We contacted those facilities when we determined what institution or state an inmate was housed in. The response we received was disheartening, and our concerns were not taken seriously.

One email we received said, in part, “We thank you for your concern and for contacting us about a perceived violation of rules and regulations within our facilities. Inmates within our facilities are not allowed access to TikTok.”

We also sent an email to the Georgia Department of Corrections, in which we provided screenshots of the inmate on TikTok, a video we captured, his name, and his inmate ID number. Two weeks later, we received a phone call.

During the phone call, we were told that the tables inmates have access to are pre-loaded with prison handbooks, motivational books, and educational materials. Other materials may be loaded onto inmates’ tables at secure kiosks, but TikTok is not one such app they can access.

Two days later, the Georgia inmate was back on TikTok live.

Many of the profiles of these inmates, on TikTok and other social media outlets, have ways in which you can send them money: CashApp or PayPal information is displayed. In other cases, cell phone numbers or mailing addresses are shown.

We contacted TikTok for comment, but they have chosen not to respond or take down the accounts we’ve identified as going live from within a correctional facility.

Loretta Hayes says seeing one of her attackers on social media felt like a betrayal.

“I was told that I would never see him again,” says Ms. Hayes. “You are sent to prison for punishment; why does he have a phone, or whatever, so he can live a comfortable life in there?”

Ms. Hayes said she has contacted the prison in which her attacker is housed. Each call ended the same, and nothing was seemingly done.

“Either he can hide that phone real good,” says Ms. Hayes, “or they [prison officials] don’t want to hear from me and don’t care to do their job.”

A prison aims to protect society by incarcerating criminals and deterring future crime. Prisons punish criminals by depriving them of liberty and not allowing them to have the luxuries life affords them, such as cell phones, tablets, or satellite television.

Many prisons fail to deter future crime, or at least the ones we’ve contacted with information about specific inmates and their access to social media and cell phones, by allowing those inmates continued access to cell phones or unlocked tablets.

If you’ve had issues similar to Ms. Hays, the first step is to contact the State Department of Corrections. You can find that information below:

State departments of corrections | USAGov

Contact your state department of corrections to learn about visiting a prisoner in a state or local prison, how to send mail to an inmate, and more.

If your issue involves a federal inmate, the information to make a report is below:

BOP: Offices

The Central Office serves as the headquarters for the Bureau of Prisons, which is overseen and managed by loading… Here, national programs are developed and functional support is provided by the following: The Central Office campus is located in Washington, DC near the U.S. Capitol, federal courts, and the Department of Justice headquarters.

We must demand change and that all cell phones and compromised tablets be removed from inmates today.